BARENDRECHT, Netherlands — It’s a warm Saturday in May, the day before the final round of the Eredivisie, and the seven pitches at VV Smitshoek, south of Rotterdam, are packed. Children of all ages are playing soccer, at varying levels of competitiveness.

Indoors, one of their youth teams is celebrating winning their league: Tradition states they’re given a vast platter of fries, followed by taking a photo with a trophy. They have 1,275 members, and teams include players ranging from 6 to 65 years old, the older generation playing walking football on an area that 80 years ago was farmland.

A 10-minute drive away is BVV Barendrecht. Their nine pitches are also packed; the clubhouse is also heaving with some of their 2,300 members. This is just a small snapshot of the Netherlands’ amateur soccer scene, and it’s here in the suburbs of Rotterdam where Inter Milan and Netherlands right back Denzel Dumfries mastered his craft.

On Saturday, the 29-year-old Dumfries will start for Inter Milan in the Champions League final, and then on to World Cup qualifiers in June. But while his Dutch teammates came through the academy pathways from a young age, shaped by the finest brains in the sport, a decade ago Dumfries was just one of the children enjoying Saturday morning soccer in this part of the world with his pals, having slipped through the academy net.

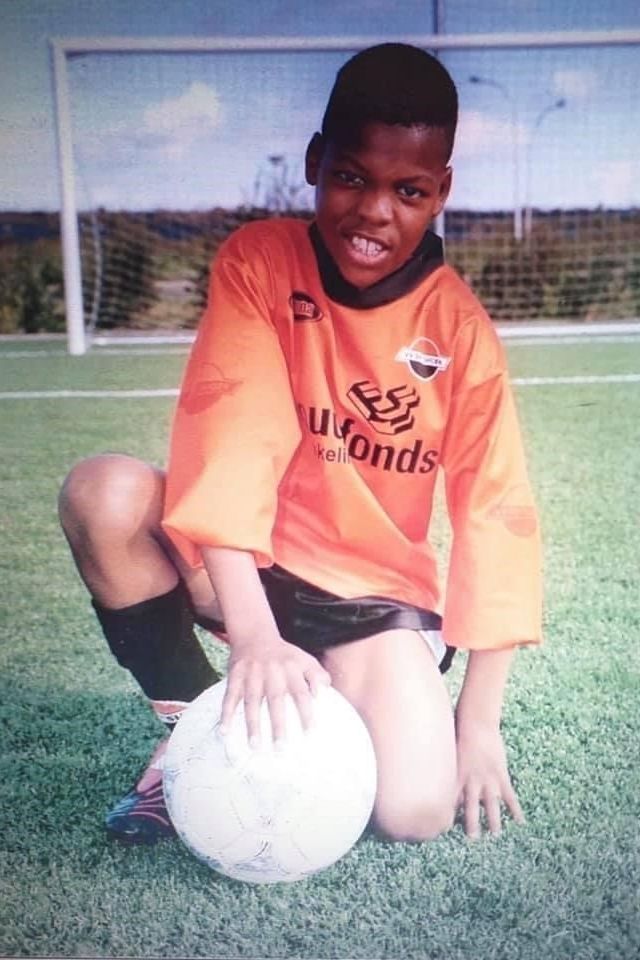

He joined Smitshoek at age 7 and played there until he was 16, telling his teammates from a young age that he would one day play for the Netherlands. They laughed at him, but he never doubted himself. “He was a child that really stands behind his dream and is willing to do anything for it,” Peter van der Pennen, his first coach at Smitshoek, tells ESPN.

It’s through hard work on the amateur soccer scene and immense self-belief that he has progressed to being one of the world’s best fullbacks. But it started in this corner of the Netherlands, on old farmland, just south of Rotterdam.

On the wall of Barendrecht’s clubhouse are shirts from graduates Dumfries, Anwar El Ghazi and Go Ahead Eagles forward Finn Stokkers. Smitshoek, who also count ex-Ipswich fullback Fabian Wilnis and PEC Zwolle’s Dylan Vente among their alumni, have two of Dumfries’ shirts in their board room, one from Inter Milan and another from PSV Eindhoven. In 2025 terms, he is a unicorn. “We have often looked at him, debated him, but we did not think he was good enough,” Feyenoord youth scout Maup Martens told de Volkskrant in 2018. “There were too many doubts about his footballing qualities. Someone can be physically very strong at 15, but that advantage often disappears when he is 18.”

“That probably has to do with his technical qualities and his height at that moment,” Van der Pennen says, responding to those suggestions. “But he had other qualities they ignored. He was fast and impressive. Every opponent was afraid of him.”

Dumfries, named after Hollywood superstar Denzel Washington, played for Smitshoek from 2002 to 2013 (bar two years when he played for nearby side Spartaan’20, only to return to Smitshoek). He then went to Barendrecht from 2013 to 2014.

Dumfries’ bedroom was in the attic of his parents’ house, and on the slanted walls, he used to draw his own expected XI for the weekend’s match. “When we were training a specific skill and it didn’t quite work, he always wanted to do it again until it worked,” Van der Pennen says. “He was also never satisfied when he was substituted; he always thought within himself he was better than whoever was replacing him. But with a sulky face he reluctantly came to the side.”

Van der Pennen remembers a match where they already had the championship tied up, and were winning, but still Dumfries chased a mislaid pass. “He failed to keep the ball in, and fell to his knees, slamming the grass, even though the match was already easily won,” Van der Pennen says.

“He was never a guy like Messi, but he was always so sure of his own ability and confident he’d get to the top,” Lesley Esajas, his coach at Barendrecht, tells ESPN. “He was overactive, he never stopped running. If he took a corner, he’d then try to get into the box himself.”

Dumfries used to regularly visit the Esajas household for dinner during the week, but Esajas remembers one day at about 17 years old when he turned down fries and mayonnaise — the Wednesday staple — as he had started taking nutrition seriously. “He said, ‘No, no, I need vegetables.'” His teammates at the time spoke of how Dumfries would skip weekend parties, focusing on his fitness instead.

Jordi Dekker, who coaches the Smitshoek under-14s, played alongside Dumfries from age 10 to 14. The team played an all-out-attack 3-3-4, with Dumfries at center back.

“There was one match where we were winning 5-4, then conceded a late, late equalizer,” Dekker says. “Denzel was furious; he grabbed the other defender by the scruff of the neck and crumpled up his shirt.” On another occasion, when he was 14, Dumfries wore an Ajax kit to a session — this is Feyenoord country, remember. Dekker adds: “His coach was unhappy and told to clean up the training field, but Denzel was on his bike straight away, riding home.”

In 2014, when Dumfries was 18, Sparta Rotterdam took a punt on him. (He also represented Aruba twice in friendlies against Guam.) He played there in the reserves — where he learned from Ajax Champions League winner and Netherlands right back Michael Reiziger — before being signed to a senior contract. “He is much stronger than me and has much more lung capacity. He can go far,” Reiziger said at the time.

Dumfries quickly received admired glances from elsewhere. “He has a lot of conditions to reach the absolute top,” Sparta coach Alex Pastoor said at the time. “Just look at his physique. If you can come on 80 times per half … those are things that ultimately make the biggest clubs in the world fall for.” Heerenveen then signed him in 2017 for a fee of €750,000. A season later, PSV paid €5.5 million for his transfer, which saw both Barendrecht and Smitshoek earn €90,000 (compensation for the work put in by amateur clubs for pro players). Smitshoek spent that windfall on revamping their clubhouse.

Dumfries progressed to become captain of PSV. “Denzel was not the player with a velvet technique, but he did have an iron-strong mentality and perseverance,” Van der Pennen says. In 2021, Inter Milan picked him up for a fee of €14.25 million. He has represented Netherlands at two Euros and the 2022 World Cup, won the Scudetto with Inter Milan last year and helped them to the Champions League final this term, including scoring twice in the semifinal against Barcelona. But he has done all this despite the academy system, which guides and molds young players in a professional environment. Matthijs de Ligt came through De Toekomst (Ajax’s academy), where he was educated and received full-time, expert guidance on every facet of his development as a player. Meanwhile, Dumfries would train twice a week after school and play on Saturday with no help on nutrition and fitness, just the knowledge of volunteer coaches helping him.

Dumfries himself said in a 2019 interview with Voetbal International: “The people who did not seen it in me were limited in their vision. They only looked at me at the time, but they should have looked further. They should have thought, ‘How can he develop?’ I think everyone should have that outlook, and not limit yourselves to something so small.”

Dumfries still holds his roots close. His parents live close to Smitshoek. He works with Lesley Esajas’ brother, Errol, on movement training — Errol visits him in Milan every fortnight. Dumfries invited them to Feyenoord-Inter Milan as his guests, and to the return leg in Milan. “He’s always working on himself,” Esajas says. “That’s why he made it.”

The day after he made his Netherlands debut against Germany in October 2018, he was opening pitch No. 9 at Barendrecht. After their under-16 side won the league this year, he sent a video message, wishing them well in their careers. “I still get kippenvel [goose bumps] watching him play,” Esajas says. “He did everything to be a star.”

At the end of this season, 10 players between the ages of 9 and 17 will move from Barendrecht into pro clubs, with Sparta Rotterdam taking three. There are usually five scouts present at both Smitshoek and Barendrecht on Saturday mornings. They’re watching players as young as 6, looking to prize them away from their friends and amateur teams to one of the pro Eredivisie sides. Both clubs have ties with Feyenoord, but that doesn’t stop Sparta Rotterdam, Ajax, PSV and countless others from dispatching eyes and ears to find the Netherlands’ next star.

It’s soccer’s arms race. Some scouts, according to sources, use devious ways to circumnavigate the agreed way of doing things, which says they need to approach the club first before talking to parents to entice their sons and daughters to join their attached team’s academies. But out of all these talented youngsters, only a pinch will make it, many will be discarded.

“The thing is, with these young players, there’s no natural progression — some peak early, some peak late,” Leen Vos, Barendrecht’s facility manager and interim head of youth coaching, says. “They need space to grow.” Even then, with every intake, scouts will ignore many of them in favor of playmakers. “These guys forget things like the importance of power and winning mentality,” Esajas says. “There are a lot of players out there like Denzel, who just need time, but scouts won’t see that. They just look for players like Frenkie de Jong. Denzel needed space to do his own thing.”

Back in 2022, on National Football Day in the Netherlands, the Dutch players wore shirts from their first football club. Dumfries opted for the orange of Smitshoek. The club’s youth program is now called “Oranje to Oranje,” reflecting Dumfries’ journey from Smitshoek to the Netherlands, according to club representative Marcel van den Eijnden. Over at Barendrecht, they still use Dumfries as an example to motivate the children who play there every weekend.

But those who have seen Dumfries’ incredible late rise from the amateur ranks to the pinnacle of the Champions League don’t think we’ll ever see the likes of him again. The rush to get talented kids into academies, and what they’re looking for, mean Dumfries will remain an outlier.

“Children don’t get the space they need to grow in football,” Vos says. “If they’re technically talented, they’ll get brought into an academy, then they’re in the system. Any wrong step, and they’re out. If they have the physical attributes but not yet the skill, they’ll be lost. What set Denzel apart was his self-belief and mindset. It’s so rare.”

Source link