BBC Africa Eye

BBC

BBCNgabi Dora Tue, consumed by grief, was barely able to stand on her own.

The coffin of her husband, Johnson Mabia, sat amid a crowd of stricken mourners in Limbe in Cameroon’s South-West region – an area that had witnessed scenes like this many times before.

While on a work trip, Johnson – an English-speaking civil servant – and five colleagues were captured by armed separatists.

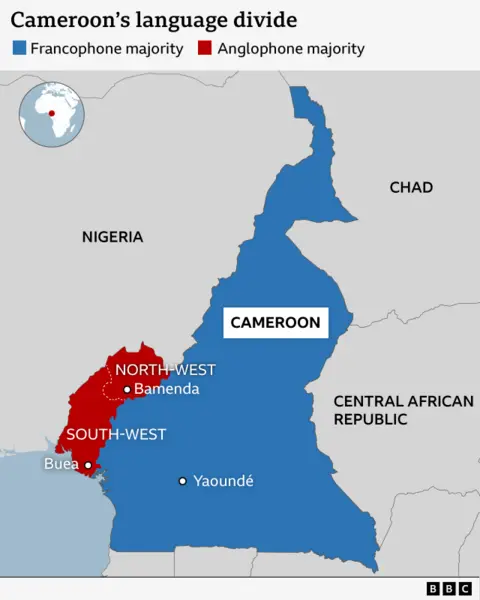

The militants were – and still are – fighting for the independence of Cameroon’s two anglophone regions in what is a predominantly francophone country. A near-decade-long conflict that has led to thousands of deaths and stunted life in the area.

When he was abducted four years ago, Dora struggled to reach Johnson. When she eventually heard from separatist militants, they asked for a ransom of over $55,000 (£41,500) to be paid within 24 hours in order to secure his release. Dora then received another call from one of Johnson’s relatives.

“He said… that I should take care of the children. That my husband is no more. I didn’t even know what to do. Tuesday he was travelling, and he was kidnapped. Friday he was killed,” says Dora.

The separatists responsible had not just murdered but decapitated Johnson, and left his body on the road.

AFP

AFPThe roots of the separatist struggle lie in long-standing grievances that stretch back to full independence in 1961, and the formation of a single Cameroonian state in 1972 from former British and French territories.

Since then the English-speaking minority have felt aggrieved at the perceived erosion of rights by the central government. Johnson was just an innocent by-stander, caught up in an increasingly brutal fight for self-determination and the government’s desperate attempts to stamp out the uprising.

The current wave of violence began almost a decade ago.

In late 2016, peaceful protests started against what was perceived to be the creeping use of the francophone legal system in the region’s courtrooms. The French- and English-speaking parts of Cameroon use different judicial systems.

The protests rapidly spread, and led to a call for the closing of shops and institutions.

The response of the security forces was immediate and severe – people were beaten, intimidated and there were mass arrests. The African Union called it “a deadly and disproportionate use of violence”.

Cameroon’s defence ministry did not respond to requests for comment on this or other issues in this article.

Armed groups were set up. And, in late 2017 as tensions escalated, anglophone separatist leaders declared independence for what they called the Federal Republic of Ambazonia.

To date, five million anglophone Cameroonians have been dragged into the conflict – equivalent to one-fifth of the total population. At least 6,000 people have been killed and hundreds of thousands forced from their homes.

“We used to wake up in the morning to dead bodies on the streets,” says Blaise Eyong, a journalist from Kumba in the English-speaking South-West region of Cameroon, who has produced and presented a documentary on the crisis for BBC Africa Eye, and was forced from his hometown with his family in 2019.

“Or you hear that a house has been set ablaze. Or you hear that someone was kidnapped. People’s body parts chopped off. How do you live in a city where every single morning you’re worried if your relatives are safe?”

There have been a number of national and international attempts to resolve the crisis, including what the government called “a major national dialogue” in 2019.

Although the talks established a special status for the country’s two anglophone regions which acknowledged their unique history, very little was resolved in practical terms.

Felix Agbor Nkongho – a barrister who was one of the leaders of the 2016 protests and was later arrested – says that with both sides now seeming to act with impunity, the moral high ground has disappeared.

“There was a time… where most people felt that, if they needed security, they would go to the separatists,” he tells BBC Africa Eye.

“But over the last two years, I don’t think any reasonable person would think that the separatists would be the ones to protect them. So everybody should die for us to have independence and I ask the question: who are you going to govern?”

But it is not just the separatists who are accused of abuses.

Organisations such as Human Rights Watch have recorded the brutal response of the security forces to the anglophone independence movement. They have documented the burning of villages and the torture, unlawful arrests and extrajudicial killings of people in a war largely unseen by the outside world.

Examples of state-sponsored brutality are not difficult to find.

John (not his real name) and a close friend were taken into custody by Cameroonian military forces, accused of buying weapons for a separatist group.

John recalls that after being incarcerated, they were given a document which they were told to sign without being given the chance to read its contents. When they refused, the torture began.

“That is when they separated us into different rooms,” says John. “They tortured [my friend]. You could just hear them flogging everywhere. I could feel it on my own body [too]. They beat me everywhere. Later they told me he accepted and signed and they allowed him to go.”

But that was not the truth.

A month after his arrest, another man arrived in John’s cell. He told him that his friend had, in fact, died in the room he had been held and tortured in. Months later John’s case was dropped and he was released without charge.

“I just live in fear because I don’t really know where to start from or where it is safe to start from or how,” says John.

You can watch the full film, The Land That Bleeds, here

Part of the separatists’ strategy to weaken the state and its security forces is to push for a ban on education which they say is a tool of government propaganda.

In October 2020, a school in Kumba was attacked. No-one claimed responsibility for the atrocity but the government blamed separatists. Men armed with machetes and guns killed at least seven children.

The incident sparked, for a brief moment, international outrage and condemnation.

“Nearly half the schools in this region have been shut,” says journalist Eyong.

“A whole generation of kids is missing out on their education. Imagine the impact this will have for our communities and also for our country.”

As if the violence between the government forces and the various separatist groups was not enough, an additional front has opened up in the war. Militant groups in the separatist areas have emerged to fight the Ambazonians in an effort to keep Cameroon united.

A leader of one of these groups, John Ewome (known as Moja Moja), regularly led patrols in the town of Buea in search of separatists until he was arrested in May 2024.

He, too, has been accused of human rights violations, of public humiliation and torturing unarmed civilians thought to be separatist sympathisers. He denies the accusations. “I’ve never laid my hands on any civilian. Just the Ambazonians. And I believe the gods of this land are with me,” he told the BBC.

Meanwhile, the cycle of abductions and killings continue.

Joe (not his real name) was – like Johnson – taken hostage by a separatist group, keen to maintain control through fear – and to cash in.

“I walked into the house, and found my children and my wife on the floor while the commander was sitting in my kitchen with his gun very close. All around me, my neighbour had been taken, my landlord had been taken. So when I saw them, I knew it was my turn,” says Joe.

He was led into the forest with 15 other people where he witnessed the execution of two of his fellow captives. But he was eventually freed after the military discovered the camp.

Johnson was not as lucky and, about two years after his funeral took place, news arrived that neither were his five colleagues kidnapped with him. Their bodies had just been found.

More families will now have to try to come to terms with their enormous loss. For Ngabi Dora Tue, sitting with her young child in her lap, the future feels almost overwhelming.

“I have debts I have to settle I don’t even know how to settle,” she says.

“I thought of selling my body for money. And then I Iook at the shame that would come after, I just have to swallow the difficulty and then push forward. I was very young to become a widow.”

The BBC has asked for a response from the Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF), which claims to be the largest separatist force.

It responded that there are a multiplicity of separatist fighters now operating in the anglophone region.

The ADF said it operates within international law and does not attack government workers, schools, journalists or civilians.

Instead it has blamed individuals and fringe entities acting on their own accord who are not members of the ADF for these attacks.

The group also accuses government infiltrators of committing atrocities while claiming to be Ambazonian fighters to turn the local populations against the liberation struggle.

More from BBC Africa Eye:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCSource link