On the same day that dozens of white South Africans arrived in the United States as refugees, at the invitation of President Trump himself, his administration said thousands of Afghans could be deported starting this summer.

Mr. Trump’s immigration policies are riddled with contradictions, epitomized by Monday’s arrival of a chartered jet, paid for by the American government, carrying dozens of Afrikaners who say they are facing racial discrimination at home.

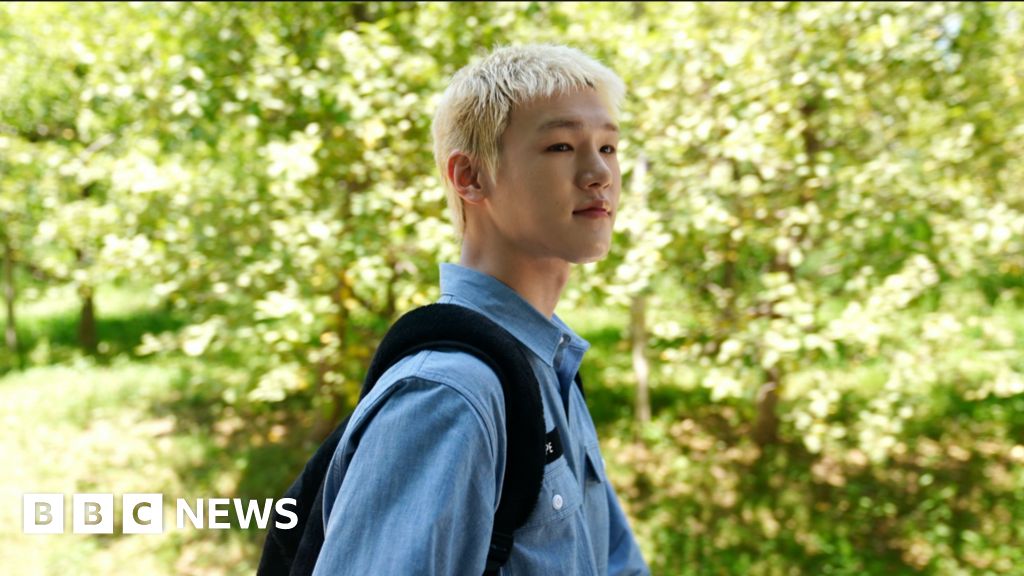

The Trump administration’s focus on white Afrikaners, a white ethnic minority that ruled during apartheid, is particularly striking as it effectively bans most other refugees and targets legal and illegal immigrants alike for deportation. Those include Afghans who were granted “temporary protected status” after the disastrous U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, many of whom had risked their lives to help American forces.

Mr. Trump’s hard line on immigration helped propel him back to the White House as voters from both parties expressed frustration over the issue. He has promised to carry out the largest deportation operation in U.S. history, and one of the first executive orders of his second term was to suspend refugee resettlement in the United States.

But the administration’s decision to carve out an exception for white Afrikaners has raised questions about who the “right” immigrants are, in Mr. Trump’s view.

Christopher Landau, the deputy secretary of state, who greeted the Afrikaner refugees on Monday, told reporters that the group had been “carefully vetted.”

“One of the criteria was that refugees did not pose any challenge to our national security and that they could be assimilated easily into our country,” he said, without elaborating on what that meant, or why other populations would not be assimilated as easily.

Asked by a reporter to explain why people from South Africa were welcomed even as Afghans were losing their legal status in the United States, Mr. Landau suggested that the Afghans had not undergone sufficient background checks, saying that the Biden administration “had brought in people that we were not sure had been carefully vetted for national security issues.”

Tricia McLaughlin, the assistant secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, said the protections for Afghan immigrants were always meant to be temporary. Trump officials have argued that temporary protected status is being used improperly, to allow people to stay in the United States indefinitely.

“Secretary Noem made the decision to terminate T.P.S. for individuals from Afghanistan because the country’s improved security situation and its stabilizing economy no longer prevent them from returning to their home country,” Ms. McLaughlin said.

Mr. Trump has long railed against refugees, claiming that resettlement programs flood the country with undesirable people and allow criminals and terrorists into the United States.

But he has made an exception for Afrikaners, who say they have been discriminated against, denied job opportunities and have been subject to violence because of their race. Mr. Trump said on Monday that the United States had “essentially extended citizenship” to them because he said they were victims of a genocide.

There have been murders of white farmers, a focus of Afrikaner grievances, but police statistics show they are not any more vulnerable to violent crime than others in the country.

Three decades after the end of apartheid, white South Africans continue to dominate land ownership. They are also employed at much higher rates than Black South Africans and are much less likely to live in poverty.

P. Deep Gulasekaram, a professor of immigration law at the University of Colorado Law School, said the exceptions made for white Afrikaners — while other groups are kept out — “overtly advances a narrative of global persecution of whites.”

The Trump administration’s reasoning for denying Afghans temporary protected status is that Afghan migrants would not face a “serious threat to their personal safety due to an ongoing armed conflict,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said in a statement. (Serious personal threats from “ongoing armed conflict” are among the specific criteria for temporary protected status in U.S. immigration law.)

Experts on the situation in Afghanistan questioned that reasoning, noting that security threats remain and that Afghans who cooperated with U.S. forces during America’s 20-year occupation remain at extremely high risk of imprisonment, torture or execution.

After U.S. forces left the country, Taliban officials said they would not carry out reprisals against people who had assisted American forces or the former U.S.-backed Afghan government.

But a 2023 report by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan documented at least 800 human rights violations against former officials and armed forces members who served under the U.S.-backed government. The abuses included “extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture and ill treatment and threats.”

Former Afghan Army members were at greatest risk, the report found, followed by national and local police officers, and people who worked in the former government’s security directorate.

“What the administration has done today is betray people who risked their lives for America, built lives here and believed in our promises,” Shawn VanDiver, president of the group AfghanEvac, said in a statement.

Source link