For people on the West Coast, atmospheric rivers, a weather phenomenon that can bring heavy rain or snow from San Diego to Vancouver, are as common a feature of winter as Nor’easters are in Boston.

Like those East Coast storms, “atmospheric river” can feel like a buzzword — more attention grabbing than just “heavy rain,” even if that is how most people walking down the streets of San Francisco will experience it. But it is also a specific meteorological phenomenon that describes the moisture-rich storms that develop over the Pacific Ocean and dump precipitation when they collide with the mountain ranges of Washington, Oregon and California.

These plumes of exceptionally wet air transported through the atmosphere by strong winds are not unique to the West Coast, though. They occur around the world, and a growing number of meteorologists and scientists are beginning to apply the term to storms east of the Rocky Mountains. When days of heavy rain caused deadly flooding in the central and southern United States this spring, AccuWeather pinned the unusual weather on an “atmospheric river.” So did CNN.

While some researchers hope to see the term become more widely adopted, not all meteorologists are doing this, including those at the National Weather Service. At the center of the debate is a struggle over how forecasters describe the day’s weather.

Atmospheric rivers can stretch up to 2,000 miles.

They form over oceans generally in the tropics and subtropics, where water evaporates and collects into giant airborne rivers of vapor that move through the lower atmosphere toward the North and South Poles. They’re distinctly narrow, on average measuring 500 miles wide and stretching 1,000 miles. Many weaker atmospheric rivers bring beneficial rain and snow, but stronger ones can deliver heavy rainfall that causes flooding, mudslides and catastrophic damage.

The rain doesn’t fall on its own. Just as water needs to be squeezed out of a wet sponge, an atmospheric river requires a mechanism — specifically, upward vertical motion — to release the rain and snow. When atmospheric rivers are pushed upward, the water vapor cools, condenses and precipitates.

On the West Coast, this process happens over and over again from late fall to early spring, and is easy to understand as mountain ranges such as the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada provide that upward lift. Atmospheric rivers coming from the Pacific Ocean smash into the mountains, causing the water vapor to rise and turn into liquid.

It’s more complicated in other parts of the country, where the upward lift usually comes from instability in the atmosphere that is less tangible — and less predictable — than a mountain. In the Central United States in early April, cold air swinging down from the north plowed underneath an atmospheric river coming in from the Gulf, pushing up that wet, moist air.

“Once the warm air lifts to a point where it’s warmer than its surroundings, it can rise explosively, and that results in severe thunderstorms,” said Travis O’Brien, an assistant professor at Indiana University, who co-authored a paper last year that drew attention to atmospheric rivers in the Midwest and on the East Coast.

The flooding was extreme in places like Kentucky, Tennessee and Arkansas — some locations recorded over 15 inches of rain — as atmospheric rivers flowed into the region for five continuous days.

Why are they called that, anyway?

Atmospheric rivers have always existed, but scientists only began to recognize them in the mid-1970s and 1980s with the development of the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites, known as GOES, which are built by NASA and operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Before that it would rain heavily on the West Coast, and no one really quite knew what was going on,” said Clifford Mass, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Washington. “Before that, we didn’t talk much about it.”

The advanced satellite technology provided the imagery that allowed researchers and meteorologists to see atmospheric rivers. They started talking about them, and naming them.

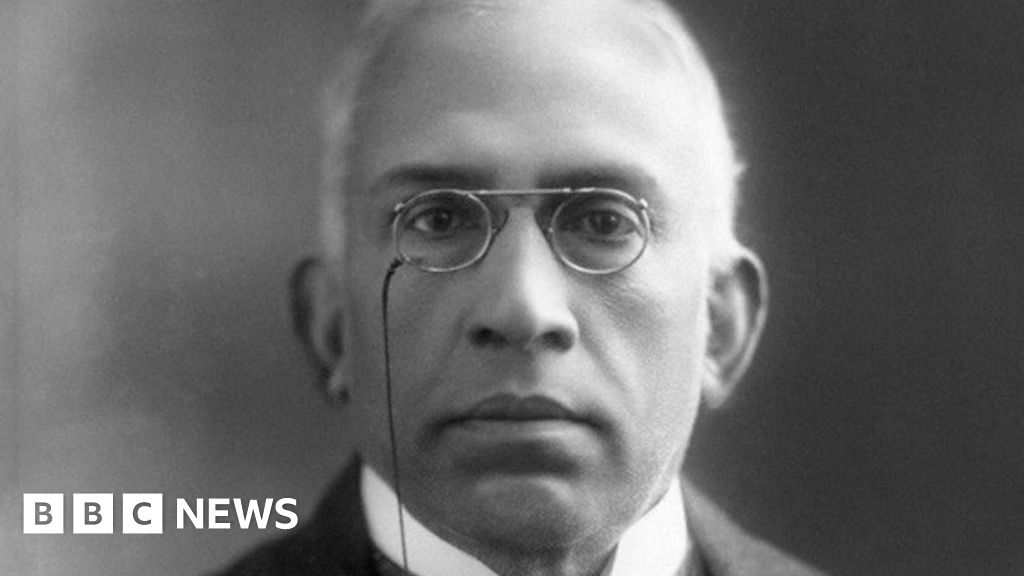

The term atmospheric river was first presented in the 1990s by two men at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Reginald E. Newell, a meteorologist and professor, and Yong Zhu, a research scientist. They at first used the term tropospheric river, after the lowest layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, where most weather happens. Two years later, that had morphed into atmospheric river, a description the men chose because the rivers “carry as much water as the Amazon.”

Is the term overused? Sometimes.

It wasn’t until the 2010s and 2020s that the term entered the mainstream, and it did so almost exclusively on the West Coast. That is because scientists were closely tracking and studying atmospheric rivers at universities there, with hundreds of research papers identifying them as a major source of rain and snow and the almost singular source of big floods in California, Oregon and Washington. One remarkable example: A series of nine atmospheric rivers drenched California in December 2022 and January 2023, causing weeks of widespread flooding and alleviating a yearslong drought.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who is known for his popular commentary on meteorology, said interest in atmospheric rivers generally surges during exceptionally wet and stormy periods in California. He likes the label but said it sometimes gets misused and overused, and that can lead to confusion around the severity of a storm. The media can mislead the public when they don’t distinguish between unremarkable atmospheric rivers, the moderate ones that bring beneficial rainfall, and the more substantial — even scary — ones that cause destruction, he said.

“The only real pitfall is this notion that all atmospheric rivers are really extreme, destructive events, because of course that’s not true,” Mr. Swain said.

A scale classifying atmospheric rivers was presented in 2019 to help alleviate this confusion. Dr. Marty Ralph, the director of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, led the development of the scale for the West Coast and has applied it in other areas of the world, including the Arctic and Antarctica. He has largely driven the research — and the marketing — of the term atmospheric river, especially in California. He and his team have written dozens of papers.

“It was Marty Ralph who sort of organized the scientific community around this idea that atmospheric rivers are a phenomenon that’s worth studying, and I think his prominence led people implicitly to associate atmospheric rivers with the West Coast, even though the original studies were worldwide studies,” Dr. O’Brien said.

That association, or lack of one, has trickled down to daily forecasts, where West Coast offices of the Weather Service will commonly discuss atmospheric rivers, but offices in other parts of the country do not.

“We don’t typically describe it that way in the Midwest and Southeast,” said Jimmy Barham, a lead meteorologist at the Weather Service in Arkansas. “We’re just going to say upper-level moisture.”

The emphasis on the West Coast has also meant that atmospheric rivers have been studied less in other parts of the country, where hurricanes and summer thunderstorms are also big rainmakers and get a lot of the attention.

Dr. Ralph hopes to see the research expand to the East Coast.

“It turns out that inside of a big Nor’easter often lurks a very strong — if not exceptionally strong — atmospheric river,” he said, “and that has not traditionally been recognized, but research is starting to document that.”

Source link