BBC

BBCIsrael’s destructive military campaign in Gaza has released a silent killer: asbestos.

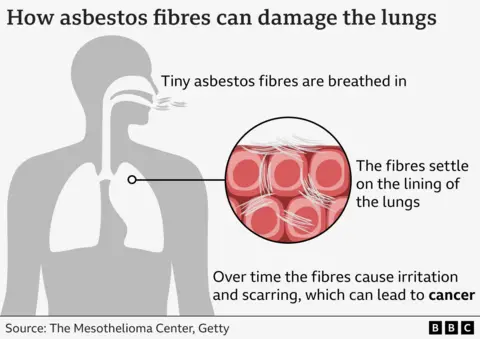

The mineral, once widely-used in building materials, releases toxic fibres into the air when disturbed that can cling to the lungs and – over decades – cause cancer.

Nowadays, its use is banned across much of the world, but it is still present in many older buildings.

In Gaza, it is found primarily in asbestos roofing used across the territory’s eight urban refugee camps – which were set up for Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes during the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli war – according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

In October 2024, UNEP estimated that up to 2.3 million tons of rubble across Gaza could be contaminated with asbestos.

“The Gaza rubble is a very, very toxic environment,” says Professor Bill Cookson, director of the National Centre for Mesothelioma Research in London. “People are going to suffer acutely, but also in the longer term as well, things that children may carry throughout their lives.”

“The lives lost now are not going to end here. The legacy is going to continue,” says Liz Darlison, CEO of Mesothelioma UK.

When asbestos is disturbed by something like an air strike, its fibres – too small to see with the human eye – can be breathed in by those nearby and can then work their way through to the lining of the lungs.

Over many years – usually decades – they can cause scarring which leads to a serious lung condition known as asbestosis, or, in some cases, an aggressive form of lung-cancer named mesothelioma.

“Mesothelioma is a terrible, intractable illness,” says Prof Cookson.

“The really worrying thing,” he adds, “is that it’s not dose related. So even small inhalations of asbestos fibre can cause subsequent mesothelioma.

“It grows within the pleural cavity. It’s extremely painful. It’s always diagnosed late. And it’s pretty well resistant to all treatments.”

Typically, those who contract mesothelioma do so 20 to 60 years after exposure – meaning it will take decades before the possible impact across the territory is felt. A higher level, or longer period, of exposure is believed to accelerate the progression of the disease.

Dr Ryan Hoy, whose research into dust inhalation was cited by the UNEP, says it is extremely difficult to avoid breathing in asbestos fibres because they are “really tiny particles that float in the air that can get very, very deep into the lungs.”

They are even harder to avoid, he says, because Gaza is so “densely populated”. The territory houses approximately 2.1 million people and is 365 sq km (141 sq miles) – about one quarter of the size of London.

Experts on the ground there say people are unable to manage the risks posed by asbestos or dust inhalation due to the more immediate dangers of Israel’s military offensive.

“At this point in time, [dust inhalation] is not something that is perceived as a worrying thing by the population. They even don’t have things to eat, and they’re more afraid to be killed by the bombs,” says Chiara Lodi, medical co-ordinator in Gaza for the NGO Medical Aid for Palestinians.

“The lack of awareness about the risks of asbestos, combined with the ongoing challenges [people in Gaza] face in trying to rebuild their lives, means they are unable to take the necessary measures to protect themselves,” a Gaza-based spokesperson for the NGO SOS Children’s Villages said.

Many are “not fully aware of the harmful effects of the dust and debris”, they added.

After a previous conflict in Gaza in 2009, a UN survey of the territory found asbestos in debris from older buildings, sheds, temporary building extensions, roofs and the walls of livestock enclosures.

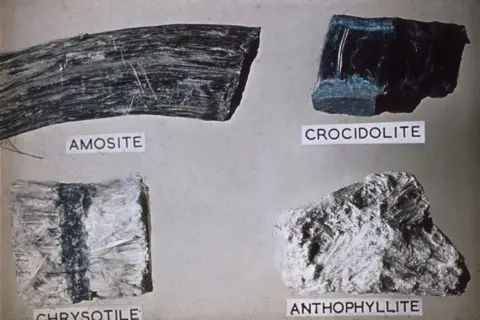

There are several types of asbestos ranging from so-called “white asbestos”, which is the least dangerous, to “blue”, or crocidolite, which is the most. Highly-carcinogenic crocidolite asbestos was previously found in Gaza by the UN.

Globally, around 68 countries have banned the use of asbestos, though some maintain exemptions for special use. It was banned in the UK in 1999, and Israel banned its use in buildings in 2011.

As well as mesothelioma, asbestos can cause other forms of lung cancer, larynx and ovarian cancer.

A further, lesser known risk is that of silicosis, a lung disease caused by breathing in silica dust, usually over many years. Concrete generally contains 20-60% silica.

Dr Hoy says the sheer amount of dust in Gaza could lead to an “increased risk of respiratory tract infections, upper and lower airway infections, pneumonia, exacerbations of pre-existing lung disease like asthma,” as well as, “emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which can be worsened by acute exposure to dust”.

For years, the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York have been used as a case-study by health experts to examine the effects of a large toxic dust-cloud on a civilian population.

“The Twin Towers were not in the middle of a war zone,” says Ms Darlison, “so it was something we were able to measure and quantify easier”.

As of December 2023, 5,249 of those who were registered with the US government’s World Trade Center Health Programme have died as a result of aerodigestive illness or cancer – a far higher figure than the 2,296 people who were killed in the attack itself. A total of 34,113 people were diagnosed with cancer over the same period.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe US and a group of Arab States have proposed competing plans for the reconstruction of Gaza. The UN has warned that the process will have to be managed carefully to avoid disturbing the vast amounts of asbestos-contaminated rubble.

“Unfortunately,” says Ms Darlison, “the very properties that made us use so much of it are the properties that make it difficult to get rid of.”

A UNEP spokesperson told the BBC that the debris removals process will “increase the likelihood of asbestos disturbance and the release of hazardous fibres into the air”.

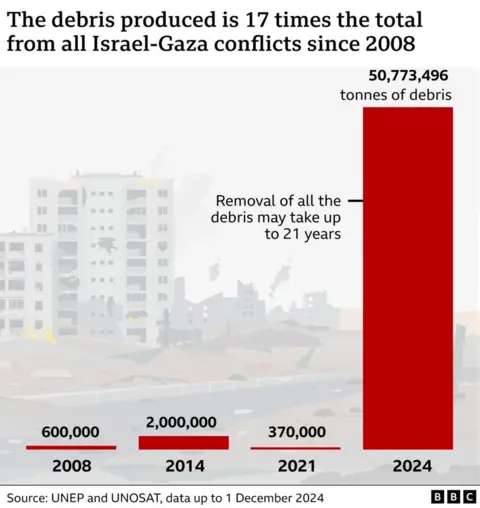

A UNEP assessment indicated that clearing all debris could take 21 years and cost up to $1.2 billion (£929m).

The Israeli military launched its offensive on Gaza in response to Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023 that killed around 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and saw 251 people taken hostage.

Israel’s offensive has killed more than 53,000 Palestinians in Gaza, mostly women and children, according to the territory’s Hamas-run health ministry.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) did not respond to the BBC’s request for comment.

Source link