Global religion correspondent in Rome

Getty Images

Getty Images“You are not alone.”

That was Pope Francis’s message to migrants on the Greek island of Lesbos when he visited in 2016. He also urged them: “Do not lose hope.”

It was in the midst of Europe’s migration crisis, when hundreds of thousands of people fleeing conflict and abuses in countries such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea sought refuge in the European Union.

What the pontiff did later that day took almost everyone by surprise.

He offered to take 12 of the most vulnerable with him on his plane back to Italy. They were selected with the help of the Catholic Sant’Egidio community, who are known for their charity work.

Among the 12 were Wafaa Eid, her husband and their two young children, who had fled Syria’s civil war.

She says Pope Francis was “like an angel”.

He let the migrants get on the plane first in order to get out of the extreme heat.

Once on board, “he came straight to us”, says Wafaa. “He put his hand on the head of my children and said: ‘Welcome.’ We were happy.”

Before his intervention she had feared her family could be sent to Turkey, following an EU deal to deport people who had arrived irregularly without official documents.

The Pope’s actions changed everything for her family.

The Sant’Egidio team helped them find accommodation and settle in Italy. Now they live in Rome where she works as a cleaner.

“My children have a future, they are studying. I work, my husband works, we have a normal life,” she says.

The Vatican said that the Pope had wanted to extend “a gesture of welcome” to refugees, rather than make a political statement. But it was widely seen as a rebuke of hardening EU policy.

The previous year more than a million migrants had arrived in Europe by sea, according to estimates from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

The IOM said more than 3,770 were reported to have died trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea in 2015 – most crossing from north Africa to Italy, and more than 800 in the Aegean crossing from Turkey to Greece.

Pope Francis argued that the solution lay with solving the problems in their countries of origin, and urged compassion for people fleeing their homes.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHis stance was not one that everyone agreed with. Italian politician Matteo Salvini said that he had a duty to oppose illegal migration.

The current Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni came to power calling for a blockade in the Mediterranean to stop migrants. She is yet to make this happen, and maintained a warm relationship with the Pope, but her position demonstrates the strength of feeling on the issue.

Three years before his visit to Lesbos, Pope Francis had also visited the southern Italian island of Lampedusa, which many migrants have used as a gateway to the EU.

There, he said Mass for migrants, condemned the “global indifference” to their plight and cast a wreath in the sea in memory of those who had drowned trying to reach Europe.

He followed that up with a visit to the Astalli Centre, in the heart of Rome, which is dedicated to caring for new arrivals to Italy. Each day its kitchen serves meals for about 300 refugees and asylum seekers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s run by Jesuits – the same religious order that Pope Francis belonged to when he was a priest – and offers services such as basic health care and legal aid, as well as help integrating into Italian society.

He arrived in a simple Ford hatchback, taking the time to pose for selfies with some of the migrants there.

“At a time when the international political situation was very unstable and was characterised by closing [of borders] in many countries, having a Pope who was on the side of migrants was a big help,” says the centre’s president Father Camillo Ripamonti.

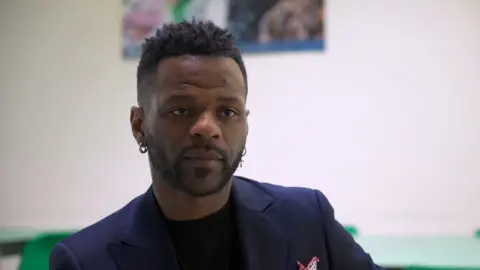

One of the people the centre supports, Cedric Musau Kasongo, is from the Democratic Republic of Congo and in 2023 the Pope embarked on an African tour which included Cedric’s home country.

He was invited to the Vatican with other migrants from each state the Pope was due to visit, to give the Catholic leader a better understanding of the situation there.

“I felt really seen,” Cedric tells me.

“Sometimes foreign people are invisible. To be in front of the Pope, to greet him, to hold his hand, for me it was a great gesture. I felt even more welcomed, seen, and heard.

“The thing that really stayed with me was his smile – when he greeted me, when he held my hand – that is the image I see when I think of the Pope.”

Source link