South East Asia correspondent

Reuters

ReutersThailand is trying to rein in its free-wheeling marijuana market.

The government has approved new measures, which will soon restrict consumption of the drug to those with a doctor’s prescription – in the hope that this will help regulate an industry some describe as out of control.

The public health minister has also said that consumption of marijuana will be criminalised again, although it’s unclear when that could happen.

Ever since the drug was decriminalised in 2022, there has been a frenzy of investment.

There are now around 11,000 registered cannabis dispensaries in Thailand. In parts of the capital Bangkok it is impossible to escape the lurid green glare of their neon signs and the constant smell of people smoking their products.

In the famous backpacker district of Khao San Road, in the historic royal quarter, there is an entire shopping mall dedicated to selling hallucinogenic flower heads or marijuana accessories.

Derivative products like brownies and gummies are offered openly online – although this is technically illegal – and can be delivered to your door within an hour.

There has been talk of restricting the industry before. The largest party in the government coalition wanted to put cannabis back on the list of proscribed narcotics after it took office in 2023, but its former coalition partner, which had made decriminalisation a signature election policy, blocked this plan.

But the final straw appears to have been pressure from the UK, which has seen a flood of Thai marijuana being smuggled into the country.

It is often young travellers who are lured by drug syndicates in Britain into carrying suitcases filled with it on flights from Thailand.

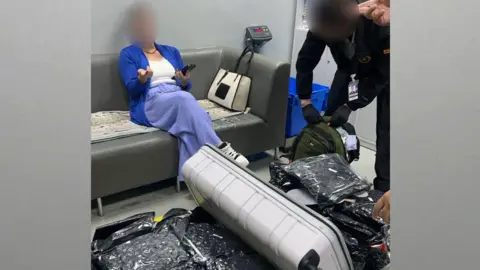

Last month two young British women were arrested in Georgia and Sri Lanka, with large amounts of marijuana from Thailand. Both now face long prison sentences.

Thai Customs Department

Thai Customs Department“It’s massively increased over the last couple of years,” says Beki Wright, spokesperson at the National Crime Agency in London (NCA). The NCA says 142 couriers carrying five tonnes were intercepted in 2023. This number shot up to 800 couriers in 2024 carrying 26 tonnes, and that number has continued to rise this year.

“We really want to stop people doing this. Because if you are stopped, in this country or many others, you face life-changing consequences, for something many of them think is low-risk. If you bring illicit drugs into the UK you might get through the first time, but you will eventually be found, and you will most likely go to jail.”

So far this year, 173 people accused of smuggling cannabis – nearly all from Thailand – have gone through the court system in the UK and received sentences totalling 230 years.

Jonathan Head/BBC

Jonathan Head/BBCThe NCA is working together with Thai authorities to try to deter young people from being tempted to smuggle cannabis to Britain. But this has proved difficult, because of the very few regulations that exist in Thailand to control the drug.

“This is a loophole,” says Panthong Loykulnanta, spokesman for the Thai Customs Department.

“The profit is very high, but the penalties here are not high. Most of the time when we catch people at the airport they abandon their luggage. But then there is no punishment. If they insist on checking in the luggage, we can arrest them, but they just pay the fine and try again.”

The legalisation of cannabis in 2022 was supposed to be followed by the passing of a new regulatory framework by the Thai parliament.

But this never happened, partly, says one MP involved in the drafting process, because of obstruction by vested interests with links to the marijuana industry. A new cannabis law was drawn up last year, but it could be two years away from being passed.

The result has been a weed wild west, where almost anything that can make money out of marijuana is tolerated.

There has also been an influx of foreign drug syndicates hiding behind Thai nominees, growing huge quantities of potent marijuana strains in brightly-lit, air-conditioned containers.

This has flooded the market and driven the price down, which is what has attracted the smugglers.

Even if more than half the people carrying marijuana get stopped, they can still make money from what gets through to the UK because of much higher prices there.

Jonathan Head/BBC

Jonathan Head/BBC“You cannot have a free-for-all, right? This became a bar fight rather than a boxing match,” says Tom Kruesopon, a businessman who was instrumental in legalising marijuana, but now thinks things have now gone too far.

“When there is a weed shop on every corner, when people are smoking as they’re walking down the street, when tourists are getting high on our beaches, other countries being affected by our laws, with people shipping it illegally – these are negatives.”

He argues that the proposed new public health ministry regulations will restrict supply and demand, and restore the industry to what it was always intended to be, focused solely on the medical use of marijuana.

There is plenty of opposition to this notion from cannabis enthusiasts who believe the new rules will do nothing to curb smuggling or unlicensed growers.

They say the measures will wipe out small-scale businesses who are already struggling because of the glut caused by over-production.

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCEarlier this month, many of these smaller growers descended on the prime minister’s office in Bangkok to deliver a formal complaint to the government, calling for a more sensitively regulated industry, and not just what they believe is a knee-jerk reaction to foreign criticism.

“I totally understand that the government is probably getting yelled at during international meetings,” says Kitty Chopaka, the most vocal advocate for smaller producers.

“Countries saying ‘All your weed is getting smuggled into our country,’ that is quite embarrassing. But right now they are not even enforcing the rules that already exist. If they did, that would probably mitigate a lot of the issues like smuggling, or sale without a licence.”

The collapse in prices forced her earlier this year to close down her cannabis dispensary, one of the first to open three years ago.

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCParinya Sangprasert, one of the growers at the protest, argues that the illegal growers are already operating outside the law in Thailand – and will ignore the new regulations as well.

He is emphatic that people cannot come to his farm and just buy 46kg (101 lbs) of marijuana – the quantity typically carried in two suitcases by the “mules” trying to reach the UK.

On his phone he brought up a copy of the official form he has to fill in every time he makes a sale.

“If you want to buy or sell a large amount of cannabis, you need a licence, issued by our government. Every weed shop must obtain this to buy marijuana, and there are records kept of which farm it’s from and who it was sold to.”

In the meantime, Thai customs officers are continuing their efforts to stem the flood of cannabis though their airports.

They are using intelligence gathered on travel patterns to target potential smugglers, and dissuade them from checking in their tainted luggage, and risking harsh jail sentences in their destination countries.

They are increasingly using the requirement for a licence to buy, sell or export quantities of marijuana to prosecute those they intercept, but the punishment is rarely more than a fine.

And the confiscated suitcases, filled with vacuum-sealed packages of dried marijuana heads, with names like “Runtz” and “Zkittlez”, still pile up in backrooms at the airports. There were around 200 in one room the BBC was allowed into, containing between two to three tonnes, taken in just the past month.

Source link